Some books I read in 2025: The Starlight Barking

More bloody children’s books! Look, I listened to some Kurt Vonnegut and had a ripping good time of it, I think that permits me to at least two adolescent “let’s see what the fuss is all about” reads.

I listened to the audiobook of The Hundred And One Dalmatians read by Joanna Lumley, and she does such a lovely job of delivering it. So gentle and sweet and pleasant, perfectly capturing the whimsical mundanity of its setting, the sort of adventure story I could see resonating with kids or folks who just love animals.

It’s only this month I’d finally seen Disney’s animated adaptation of 101 Dalmatians… and I feel like I missed my moment with it. It’s perfectly charming and beautifully animated, but it also made little impression on me? I feel the book did a much more compelling job of giving us a glimpse into the world and mindview of canines, courtesy of conversations between them or insight into their thought processes.

You gotta trim that fat to work in a visual medium, of course, but Disney’s fare just comes across like your standard animated adventure, because how do you set apart an animal-centric story from all your other animal-centric films? Though I might’ve spoilt myself watching The Aristocats first as a kid; it’s hard to top Scatman Crothers literally bringing the house down with a raucous jazz number.

(that, and the film opening with Pongo ogling a bunch of women and trying to hook up his owner with one probably didn’t win me over. I used to look at that great tongue-lolling expression and think, what a great piece of emotive cartooning, but knowing the context I can’t not think “that dog is hornyyyy”)

Disney’s obviously had a good run with it, with a live-action adaptation, at least two sequels, a cartoon series, a newspaper comic strip, and more I’m probably forgetting (I was tempted to watch Cruella to give myself more to talk about in this post, but I couldn’t last ten seconds, sorry).

But it does give the impression that without the author’s distinct style of gentle narration, the vibe of the whole thing shifts. Disney’s depiction has dominated its perception, that it’s perhaps why its literary sequel, The Starlight Barking, is so perplexing to folks when they learn about it.

I won’t lie, it is an odd one! All the dogs in the Pongo household wake up, but none of the humans do. Nor the cat, nor the birds outside, not even the cows in the barn. They’re breathing and smiling blissfully in their sleep, but no amount of barking or rough-housing will rouse them. What’s going on?

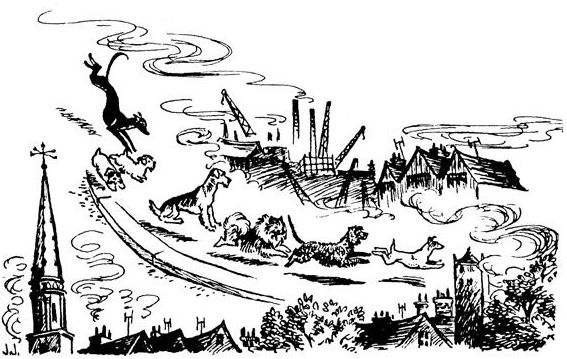

Worried how they’ll be served food without their owners, the dogs soon discover they can do things simply by thinking, from opening doors to switching on lights, to even gliding across the ground, or “swooshing” as they call it. They can even communicate without the need for barking, thoughts transferred across great distances so long as they know who they’re speaking to. All that, and they’re not even hungry or thirsty!

Despite the stakes in both books, there’s a certain gentleness about the whole thing — as perilous as the journey towards Hell Hall is in the first adventure, there’s some reminder of the goodness in people every step of the way, knowing that they’re not in this alone.

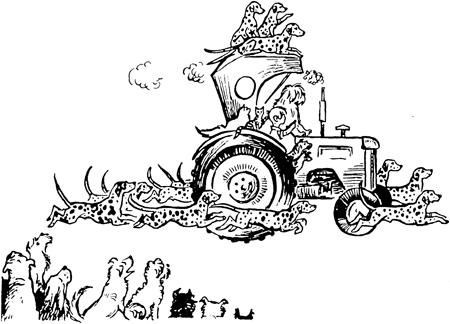

Likewise, although Starlight Barking is set to the unsettling atmosphere of a world gone quiet, the frivolity the dogs have in figuring things out and troubleshooting idle conundrums is extremely charming. The ‘honorary dogs’ inducted in the last book, the cats and the Colonel’s infant aide, are awake but do not have access to these new powers, so how are they to make the journey to London? By having the dogs carry a tractor like a sleigh, of course!

The prose is so pleasant and whimsical, yet for as fantastical as the events might seem, there’s a dream-like tranquillity to it all. I was still hearing Joanna Lumley’s narration in my head reading it, there’s such a delightful flow and cadence to its prose.

The dalmatians we know remain their colourful selves, like Missis’ penchant for misreading turns of phrase, and between the grown-up pups and the dogs in parliament, there’s still new faces and dynamics to get acquainted with; the pint-sized Cadpig now lives with the Prime Minister, and takes a position of authority amidst all this kerfuffle. For as larger-than-life as the events may be, it never loses track of the characters participating in them.

The book does frequently address the events of the first story, with an aside where they suspect Cruella De Vil is somehow responsible for all this, only to break into her house and find her fast asleep like everyone else, having changed fashions from fur to tin. It’s absurd, the kind of image you’d encounter in a weird dream, but treated so simply and sweetly.

90% of the affairs are an idle mystery, household animals flailing around to figure out what’s the root of this problem, and how their new powers might assist in solving mundane problems in the interim. It’s a fun ride the first time, though I don’t know how well it’d read on a revisit, seeing how it’s all leading to an ending that dwarves everything prior.

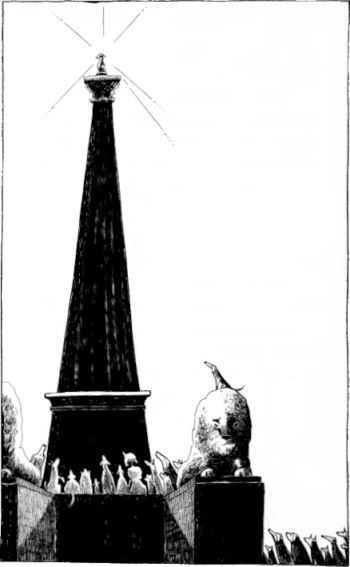

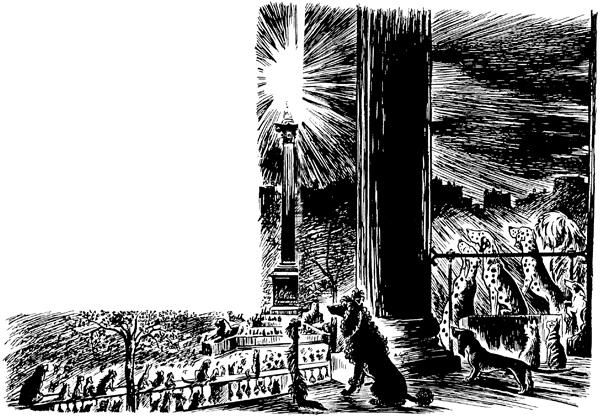

Come the second night with still no answers, they turn on the television and a great light speaks to them with the voice of their masters, introducing himself: he is the Dog Star, Sirius. He warns them that because of war-mongering, squabbling humans, Earth is at the brink of self-destruction, and offers canine-kind the chance to come with him to the Dog Star. There they will be happy and blissful, but nothing else on Earth will come with them; the humans will remain behind, with no memory or knowledge of any of the dogs in their lives.

The first book had a little aside when the puppies rest in a chapel, believing it to be tailor-made for them, with soft pews just the right size and even its own little “television”, actually a manger scene, Cadpig remarking, “I like it much better than

ordinary television. Only I don’t know why.”

This second book has a recurring phrase of “wait and see” in response to any potential fears, feeling like something from Britain’s WW2 playbook of not knowing what the future may bring, but not getting your knickers in a twist is the most important priority. Mustn’t look unbecoming when the fascists steamroll in, pip pip. It all evokes a “Queen and country” motif, that whether they’re conscious of it or not, there’s a trust in the higher powers that they know what’s best and can be trusted.

Despite the initial confusion, there’s an undercurrent of it as an almost “heaven on earth” scenario. There’s no hunger, there’s no fatigue, and everyone’s obedient; they’re all waiting to hear on Cadpig, she’s the authority around here. Despite all the dogs packing into London seeking answers, there’s no scraps or squabbles, something they’d expect when everyone’s crowded and confused, but everyone’s pretty chill and happy taking orders.

It’s only when a higher power shows up that some dissent begins to enter; after all, nobody knows what’s going on, but there’s been no actual stakes or problems thus far, aside from hoping their humans will be alright.

But being dropped a bombshell like this by an entity who tries to appear trusting, manifesting as each dog’s respective breed with the voice of whom they respect most, it causes a bit of furor once they discuss and realise the disparity. Why would someone who claims to have our best interests in mind do something so deceiving? The dogs discuss amongst themselves, even hearing from dogs who freed themselves from shelters or are strays, and the consensus seems to be: we stand by our humans. Either we are loved and cared for already, or holding out hope for someone who loves us to take us in. This is our home, and we do not wish to leave it behind.

And the whole thing suddenly reads like a religious parallel. Would you go to heaven early at the expense of everyone forgetting about you in the interim? You will have no wants, needs, or worries, and no longer be bound to earthly limitations, but is life worth living without its peaks and valleys? Is it worth it going to heaven if you may lose everything and everyone you loved in life?

It makes up only two or three chapters, but it’s a really interesting argument! Every dog has been swayed by the feeling of bliss Sirius radiated, but seeing the discussion and rebuttals brought up amongst themselves, the consensus seems to be that they’re committed to the life they know.

Missis is a notorious big eater, so getting served breakfast is the first of her concerns at the story’s beginning, but it subsides once they realise thirst and hunger are no longer a concern… yet she misses the feeling of being hungry. Her takeaway from Sirius’ offer is: is living in a state of permanent bliss really bliss at all? He proposes it like a binary state, but to her, looking forward to a good meal, and the satisfaction of finally eating, they are all little blisses in themselves, feelings that cannot be rolled into an all-encompassing state of happiness.

I’d read a few books recently that lightly tackled the unease of post-war Britain; memories of the threat of bombing, the ongoing need for rationing, and the quiet fear of if we’ll still have a world as we know it going forward. Simon Winder’s novel essay on the James Bond franchise, The Man Who Saved Britain, really dives deep into the matter and the desire for escapism — in Bond as its frivolous luxuries and casual globe-trotting, but later in science fiction, proposing worlds and possibilities that are no longer beholden to our earthly limitations.

The Starlight Barking feels like Dodie Smith’s attempt to dip her toes into the sci-fi genre (as it was defined in the 1960s, before whiz-bang space opera became the standard), with Missis outright discussing the subject as they explore their master’s library for clues, falling on “metaphysical” as their catch-all explanation for how and why these things are possible.

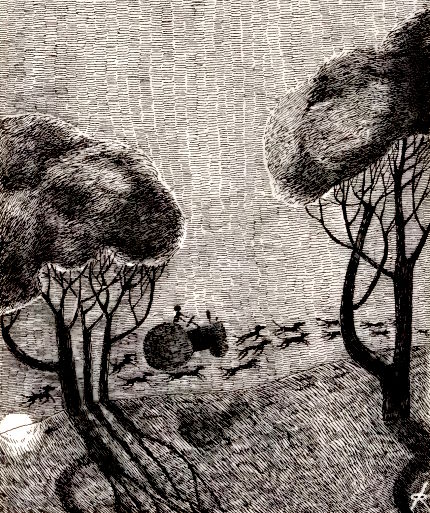

The dogs politely decline Sirius’ offer, and he departs, promising to undo what he has done come sunrise: the humans and animals will wake, the dogs will no longer have their powers, and there will be memory of these events having occurred. This results in everyone having to scramble back to their homes, as their speed will expire come dawn, yet the way they fret about it, it feels like there’s some unconveyed threat to not making it back in time.

Rolypoly has been missing for most of the story, and Missis refuses to go home without him, pleading to go back and look, but Pongo keeps urging her to move forward, they have no time to stop and search… and maybe it’s because the image in a storybook messed me up as a kid, but it brings to mind Lot’s wife looking back upon Sodom and turning into a pillar of salt.

Missis is so rightfully worked up about his whereabouts, and Pongo is so adamant they focus only on moving forward– it’s stressful! It’s worrying! It’s rare that the loving couple are in actual disagreement like this, and with the fear of an actual god smiting them or something, we don’t know what the ramifications are for disobeying!

It turns out Rolypoly had been gallivanting in France this whole time with the foreign minister, a strange bit of comic relief after the story’s first genuine spike of tension. Everyone gets home safely and the world wakes up as usual come morning; Pongo knows he can’t share the tale of their adventure with the humans, nor will he even remember it soon. It’s a pleasant enough little ending once you get past a mother’s fear of what divine punishment might await her son.

I do think we’re so franchise-brained in this day and age, that we’re afraid of making bold moves like this. A star, a literal star, has come down and said, hey, your owners might fucking blow up the earth. I’m not gonna stop them, but you, the dogs, I’m gonna save you guys. And in the interim you’ve got dogs flying at 30 miles an hour, and only near the end do they figure out they can levitate too, so you’ve got vertical lanes of four-legged traffic swooshing around London streets. How do you go forward from this experience?!

Again, the first book felt very grounded despite its ridiculous characters and circumstances, courtesy of its gentle pace and easygoing prose. The stakes and scope are relatively minor in the grand scheme of things, but it’s a monumental undertaking for a pair of dogs who’ve only known breezy walks around the park. Even amidst the reconnaissance and their rescue mission, they still have to be aware of the permissions and suspicions placed upon dogs, so to speak.

They can’t be seen without their collars at risk of being perceived as strays, and after the thrill of escaping Cruella’s sight by covering themselves in soot, there’s a real fear that their owners won’t even recognise them once they return home — it’s a silly fear, but if you’ve owned a dog, you could imagine such a thought would genuinely wrack its poor little head. Even if it’s just in the background, there’s a constant interplay between the world of humans and dogs, figuring out what they can and can’t do, and using the perks of both worlds to their benefit.

So The Starlight Barking stripping away a lot of those mechanics does make for an arguably simpler story — figuring out what to do and what they can do is a journey in itself, but the world is effectively a sandbox now. There’s no humans to interfere or intervene, thirst and fatigue aren’t an issue, it’s just two days of snooping around before the answer literally presents itself to them. It’s admittedly the type of story where the journey is greater than the destination.

In truthfulness, it comes across like the type of story you’d get if you broached a child with a subject: What if there was a world with no humans, it was all just dogs and their inducted dog-adjacent friends? What can they do, how would they get things done? They’re still dogs, they can’t operate machinery. Even a clever dog like Pongo still struggles to open doors.

Well, they think the things they want to do, obviously. A dog’s not going to know about nuclear physics, but it knows things like “I want to go there” or “I want to move fast;” the streets of London are lit up at night because they realise they need to see their surroundings, so the deed is done. It’s a child’s answer to problem solving.

I say that without a whiff of disparagement or snottiness — I think it’s whimsical! The imagination of a child is fascinating to me, weird and wonderful in ways you wouldn’t expect, and I could imagine being read this as a youngster would stir the mind, left to ponder what might happen next at the end of each chapter.

The book ends with a fairly la-di-dah tone, unfortunately close to “it was all a dream,” but I could see a kid latching onto the possibilities. Pongo and Missis are smart dogs, surely they won’t forget! What can they do with that knowledge? They made it from London to Sussex in their last adventure with a little help from their friends — could they chart a course to Sirius and give him a piece of their mind…?

I can understand this book reading like it’s got an identity crisis for some folks. It loses the mundanity of its real world setting by writing humans out of the equation, leaping straight into science fiction… but it’s not really science fiction, it’s still steeped in magic and whimsy, canine brains brushing at the fringes of higher concepts. And the big reveal at the end, the one part everyone talks about, is such a swerve into melancholy and philosophy, at least in my eyes, that it suddenly becomes a different story altogether. It’s an odd one!

Yet I also think it’s the most interesting follow-up you could make? Again with the franchise brain, I don’t know what more you can do with the foundation set up by that first story. All I can envision is just The Famous Five but with dogs, which seems in-line with Disney’s output. That’s probably what people want, right? Before easy access to puppy videos, this is the sort of stuff dog moms had to settle for.

I’m speaking out of my arse a bit, but Starlight Barking almost feels like an Edgar Rice Burroughs speedrun: Establishing its core characters and concepts in the first book, only instead of spending years serialising adventures with Tarzan’s growing family and notoriety, it dives straight into the bit where he’s fighting giant ants at the Earth’s core or whatever the fuck. You could give it a bit of leeway if it were the sixth book in a series, a few more misadventures or scrapes with Cruella to set a precedent, but as the one and only follow-up by its original author, I can understand people being left a bit confuddled. I repeat, how did we get here?!

There doesn’t seem to be the same behind-the-scenes drama behind 101 Dalmatians’ Disney adaptation as there was with Mary Poppins; part of me was wondering if The Starlight Barking was like a screw-you to the company, “let’s see them try and adapt this!” But I figure it’s simply the author exploring the concept as far as she personally wanted, and that I respect.

It’s a perfectly charming read, and abstracted as it may be, I find it a novel and exciting way to follow up on the foundations of its predecessor, exploring the minds and whims of canine-kind in a far more whimsical scenario than just another dog-napping case. It’s the kind of out-there extrapolation of themes and scope I’d like to see in more sequels, though I understand I might be a freak and an outlier for thinking that. Internet listicles and trivia geeks have spoiled the novelty of it, but I’d say it’s worth a goosey.