IN WHICH 3D PLATFORMERS

ARE A MYSTERY

YET TO BE SOLVED

The early-to-mid 90s were a good time for 2D platformers. Between the back-to-basics approach of fare like Donkey Kong Country or Pitfall: The Mayan Adventure, mixing old-school gameplay with sheer depth of secrets to find and lush graphics, there was fare like Yoshi's Island or Sonic the Hedgehog 3, which pushed their formulas further than ever with fresh gimmickry and strong core design. They weren't all winners, but it was a fun and adventurous era!

On top of that excitement, there was the coming age of next-generation consoles, touting specs that could finally begin to rub shoulders with arcade hardware of the time, and perhaps most importantly: full 3D capabilities! No longer are we stuck with a measly two dimensions! Now we've got a Z-axis to play around with!

Power Drift (1988)

Of course, this anticipation also came with a lot of teething pains and soul searching. How would one even design a game in true 3D space? It's telling that in arcades, where the beefier hardware held greater potential for 3D games, they focused primarily on 'vehicle' games, be it the vector-based space-shooter Star Wars way back in 1983, to SEGA's Virtua Racing.

SEGA had a long history of "super scaler" titles, using a fast flurry of hardware-scaled sprites to simulate forward 3D motion, across shooters like Space Harrier or After Burner, to their long history of driving and racing games. To go 3D was to simply cut out the middleman, to take away the shadow puppetry and just put actual-ass dragons in front of your face. I think I lost the analogy I was going for.

That's fine for vehicle games, which have long fought to simulate the rush of 3D movement (within the confines of a track, of course), but what about all the other genres? Fighting games, platform games, and so many others have managed just fine without the third dimension... but what if, though? How would you translate such familiar left-to-right, hop-and-bop gameplay into a medium that gives you greater depth to explore?

If you want to be pedantic, 3D platformers had already been explored in comparatively obscure PC platforms, perhaps most notably Christophe de Dinechin's Alpha Waves, released circa 1990. Ostensibly an evolution of room-based puzzle games like Knight Lore for the ZX Spectrum, wherein comprehending 3D space with such limited detail was as much a part of the game's puzzle elements as finding keys to unlock doors.

Jumping Flash is perhaps the first breakout 3D platformer on home consoles, hitting PlayStation in April 1995, and a very experimental one at that. Using the 3D presentation to its fullest, the game is not played with a visible avatar of your character on-screen, but instead all of the action is viewed through Robbit's eyes -- not just a 3D platformer, but an even-rarer first-person 3D platformer!

This was absolutely a head-turner, and arguably a key part of the PlayStation's identity in its formative years. First-person presentation was in! Between this, Ridge Racer, and dungeon-crawlers such as King's Field or Crime Crackers, embracing the 3D immersion head-on was the new hotness, viewing everything through digital eyes.

Gameplay-wise, Jumping Flash goes back to the roots of platforming; before Super Mario Bros., but to arcade fare like Bomb Jack, wherein the goal is to collect the items required to open the exit. By virtue of exploring such self-contained worlds via Robbit's viewpoint, what would otherwise appear like a single-screen arcade game becomes an immersive experience, completely reimagining such simple movesets as high jumps or the ability to leap multiple times in mid-air. You'll believe a rabbit can fly! Or close enough!

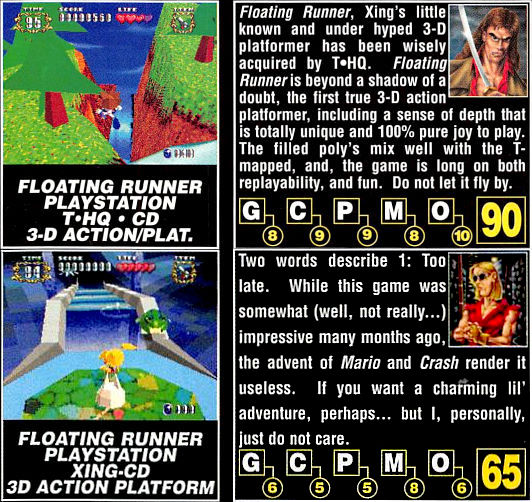

A lesser-known PlayStation-exclusive arrived at the dawn of 1996, Floating Runner, another striking game with its mixture of chibi anime illustrations and adorable, flat-shaded, low-poly graphics. It takes on a more familiar approach, following a human-shaped protagonist from a third-person perspective, albeit with a strangely zoomed-in camera, and simply tasks you with getting to the stage's goal; this is before collect-a-thons were the name of the game. Coming from the mad lads at T&E Soft who brought you Virtual Hydlide, it's more capable than you might expect.

top: GameFan Volume 4 Issue 4 (April 1996)

bottom: GameFan Volume 4 Issue 11 (November 1996)

Although decidedly lo-fi and limited in scope (the camera certainly did its damnedest to rein in any wanderlust), the game was a simple but earnest attempt at broaching the concept, tackling the concept at its most base level. What sunk its chances of making a splash was... timing. The reviewers at GameFan were incredibly smitten with the game when they imported it in April 1996, but by the time it reached western shores in November, it had already been trumped by the newcomers who'd inserted themselves at the top of the food chain.

The Nintendo 64 (né Ultra) finally hits shelves in Summer 1996, and with it a complete reimagining of a staple of 2D platforming: Super Mario 64. What is there to say? Gone is the linear hop-'n'-bopping of Mario of olde. Gone are the points, the conventional power-ups, and simplistic inputs of the NES titles. Nintendo looked at the possibilities of 3D and tackled it head-on, thrusting Mario into large, expansive worlds to explore in every possibly direction -- up twisting mountains, down dark waters, or even all directions at once with his new Wing Cap power-up.

Ignoring its gummy polygonal takes on classic characters and archetypes, there's very little in Super Mario 64 that resembles its classic games. There are power-ups, but they're presented more as puzzle-solving devices than power fantasies. Each stage technically has a beginning and end, but only if you know where the Power Star is -- levels are open-ended with no shortage of paths to take, and if you don't cotton on to the challenge that's asked of you, you could be wandering around for a long, long time. This kind of explorative approach was by no means new to 2D platformers, but it was pretty fresh to Mario, and a jarring new venture into realms unexplored.

Three months after that on PlayStation, a new mascot hit the scene; developed by a bunch of screw-ups with only obtuse adventure games and a dodgy fighter in their repertoire, a sudden infusion of budget allowed them to set their sights on tackling 3D. Crash Bandicoot is relatively back-to-basics compared to its competition; its mechanics are simple, sticking to the Sonic the Hedgehog or Donkey Kong Country school of thought where jumping and bashing into things are your primary means of interaction.

Rather than wide-open spaces, it focuses on 3D through its iconic visual of running 'into' levels -- levels are linear with a presentation not unlike classic 2D platformers, where everything that's on-screen is all you have to contend with at the present time. It plays with this in iconic setpieces like the boar-riding or boulder chases, forcing you to react quickly to rapidly-incoming hazards, or even run towards the camera, giving a cinematic presentation as you react to dangers moments before you bang into them.

Although hard as balls, this game set a great impression on the new era of 3D. Easy to pick up and play for players of all ages and skill levels, because what's not to understand? The linear levels are easy to parse, and its bevy of secrets harken to the likes of Donkey Kong Country, where there's no shortage of extra challenges to be found down conspicuous pits or platforms. Even the cartoon presentation did wonders for it; the hand-animated 3D models looked like caricatures, boasting great levels of expression thanks to their individually-tweaked polygons.

Even the frustration at dying was somewhat mitigated thanks to its Looney Tunes-esque animations: Crash squashing like a pancake, getting blowing to smithereens, or simply falling to his doom with a trailing whistle. The N64/PlayStation era arguably ushered in a new era in '90s 'tude, and Crash was probably the instigator.

Although rarely counted alongside the cutesy animal contemporaries, Lara Croft is very much a mascot of her own making, and also a distinctly modern take on the platforming. Owing more to the likes of Prince of Persia than our plumber paisano, Tomb Raider made an identity for itself on how seemingly 'adult' it was -- although still built on boxy polygonal grids, its moody environments and sense of mystery and exploration created an atmosphere so unlike what could be accomplished in 2D.

That, paired with its somewhat generous representation of a polygonal pinup model, helped usher in the PlayStation's attitude of "games aren't just for kids!", with Lara's busty figure adorning everything from magazine covers to energy drinks. But I digress!

One of the game's biggest standouts was perhaps its unique control style. Rather than Mario and Crash's free-form input wherein the character would move in the direction pressed, Lara would instead be 'steered' and told to run forward or back-pedal, somewhat akin to steering a tank. Although perhaps a bit uncanny compared to the more 'immediate' action of its competitors, it fit the motif.

Its levels were large, sprawling, and often maze-like, where simply figuring out where to go next, be it via complex jumping challenges or solving puzzles, was more key than blindly running forward. With the slower, methodical approach to gameplay and the camera locked firmly behind Lara most of the time, it made a fitting vehicle for its grandiose approach to 3D space, one where scale and verticality played a big part.

advertisement from GamePro issue 97 (October 1996)

advertisement from GamePro issue 97 (October 1996)And then... there's Bubsy 3D. Oh, poor Bubsy. Released November 1996 and forced to compete against the other heavy hitters that Christmas season, it didn't make a good show for itself. Bubsy already boasted huge, expansive levels with almost outrageous levels of verticality and tiers to explore, so to take that to the third dimension seemed a no-brainer. Just do that but with an extra axis, right?

Unfortunately, the speed and immediacy of that game is chucked out in favour of sluggish tank controls; a necessity given the extremely precise and precarious platforming it demands, but no less of a killjoy. Where Lara's controls were smooth and graceful, Bubsy's were juttery and unpleasant, moving with as much grace as a cat stuck in a letterbox. While it retains a few individual aspects from the classic games, the package leaves a lot to be desired.

Sacrifices have to be made in converting classic 2D characters into 3D space, but it's hard to say whether the changes were worth it. Mario 64 ushered in a new genre unto itself with competitors iterating on its foundations. Bubsy 3D's just kind of abstract dreck.

Had it been released a year prior it could have been remembered as an early formative point in the genre, but to be released after history had already been made probably cut it off at the knees.

Perhaps what Bubsy 3D is best known for ('best' used pejoratively here) is its sheer abundance of dialogue. Anticipating the teething pains in navigating 3D spaces, the game is rife with hint bubbles that prompt Bubsy to vocally explain each of the game's commands and quirks, from the completely arbitrary first-person-shooting mode, to the various collectibles, and whatever the hell else.

Although it lends the spark of life to what are otherwise jarring alien environments, it only makes the game's soundscape even worse, with Bubsy constantly barking sarcastic instructions at you. This, sadly, is an unfortunate omen of gaming to come. Do you enjoy endless tutorials? Do you like your game's characters to be nattering endlessly at you, spewing words without a whit of worth in them? Buddy, you ain't seen nothing yet...!

3D PLATFORMERS THUS FAR...

1995/04 Jumping Flash!

1995/08 Bug!(?)

1996/01 Floating Runner: Quest for the 7 Crystals

1996/04 Jumping Flash! 2

1996/06 Super Mario 64

1996/09 Crash Bandicoot

1996/11 Cheesy(?)

1996/11 Bubsy 3D

1996/12 Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire(?)

1997/02 Tomb Raider

1997/03 Doraemon: Nobita to Mittsu no Seireiseki

1997/06 Willy Wombat

1997/09 Croc: Legend of the Gobbos

If you want me to be extremely anal, I could discuss the also-rans. Cheesy and Bug! barely count as 3D platformers; the latter a maze game with perspective, and the former using it solely as a clumsy level select. Willy Wombat's a gem, though, and I won't tolerate anyone calling it a bad game, however right they may be.

Shadows of the Empire is a fascinating kick-off to the blossoming "kitchen sink" genre, mixing 3D platforming with third and first-person shooting, ground-bound and fully 3D vehicular stages, as well as limited bouts of total aerial freedom... making it hard to discuss without addressing those genre evolutions as well!

I was under the mistaken impression Doraemon on N64 was developed by Hudson Soft (they were responsible for the robot cat's adventures on Famicom and PC Engine), in which case I wanted to draw unfounded parallels between it and late-era Adventure Island titles... but it's not, and I've very little to remark on it otherwise. I'm not sure why I got that idea, honestly.

Nintendo magazines of the day dismissed it as a cheap Mario clone. Is there much truth in that? Who knows! Who cares! This preamble's gone on long enough! Sorry to chuck a beloved mascot under the bus, but we've got a game to dissect!

Come September 1997, a new character hit the Sony PlayStation and SEGA Saturn...

![and now you know where the heading motif came from IN WHICH A CROCODILE IS FOUND

It all started one morning in the third month of the Year of the Soupspoon [1]. King Rufus the Intolerant [2], ruler of the Gobbos, was down by the riverbank watching the sunrise. He had just finished breathing a sigh of relief that, once again, the sun had returned, when suddenly a small basket floated ashore. He and a group of his Gobbo subjects huddled around it. Peering inside, they saw a baby crocodile. Naturally, they assumed he must be the early leader in the Annual Midget Crocodile Basket Race. Not that there had ever been such an event, but you never know about these things, and many of the Gobbos placed bets just to be on the safe side. After a couple of hours, when no other baskets had come by, the Gobbos decided that perhaps there was no race, or that it had been called off the night before by crocodiles who shared their concern that the sun had gone away for good.

[1] At the start of each year, the Gobbo high priestess would announce the kitchen utensil that, when put down their pants, would bring good luck. Gobbos took this very seriously, although some began to question the practice during the Year of the Electric Can Opener.

[2] People far and wide had heard of King Rufus the Intolerant and feared him for his name alone. Of course, the Gobbos knew his full name was King Rufus the Lactose Intolerant and therefore only feared him after a big bowl of cottage cheese.](img/manual.jpg)

back

back